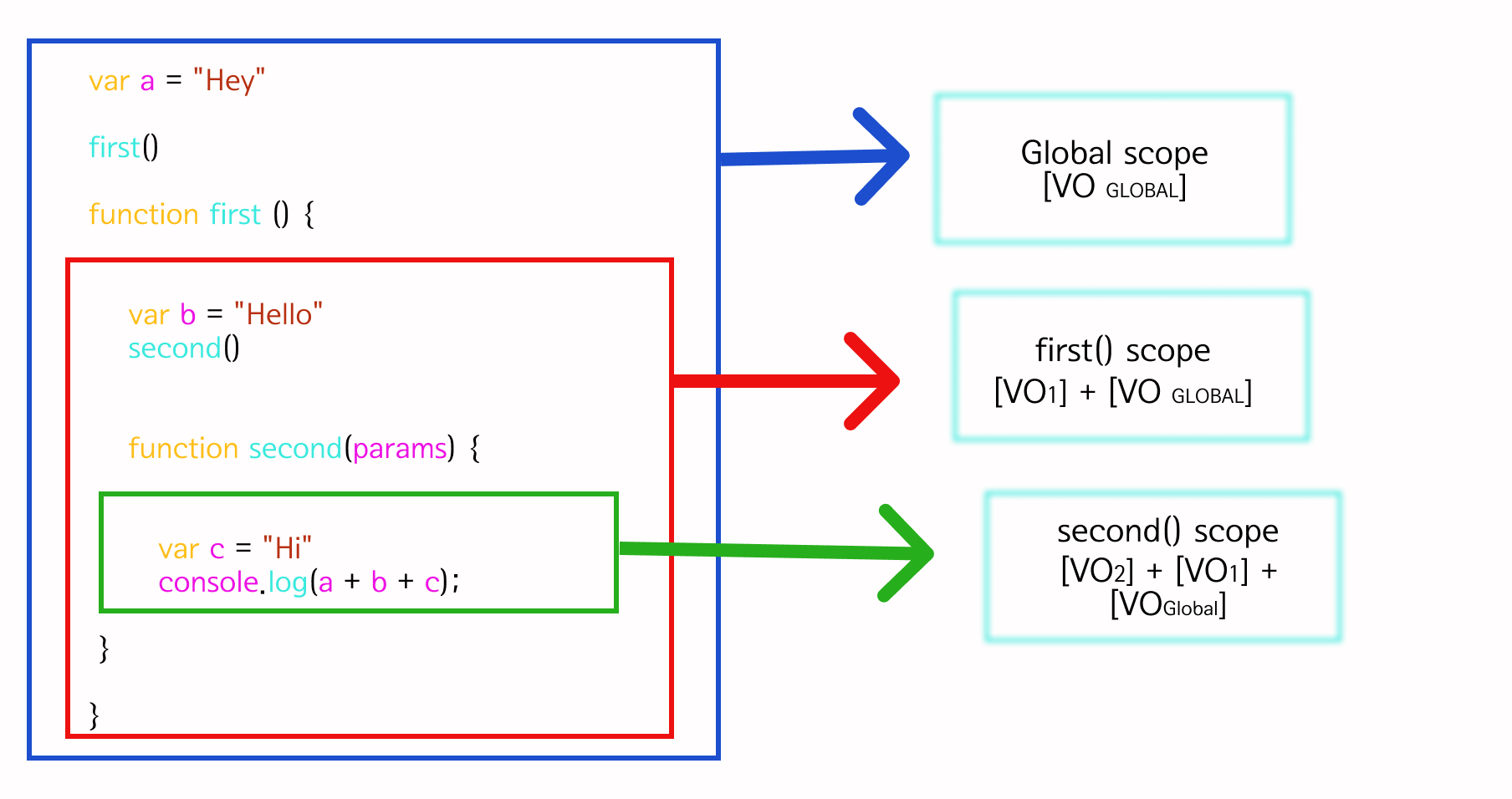

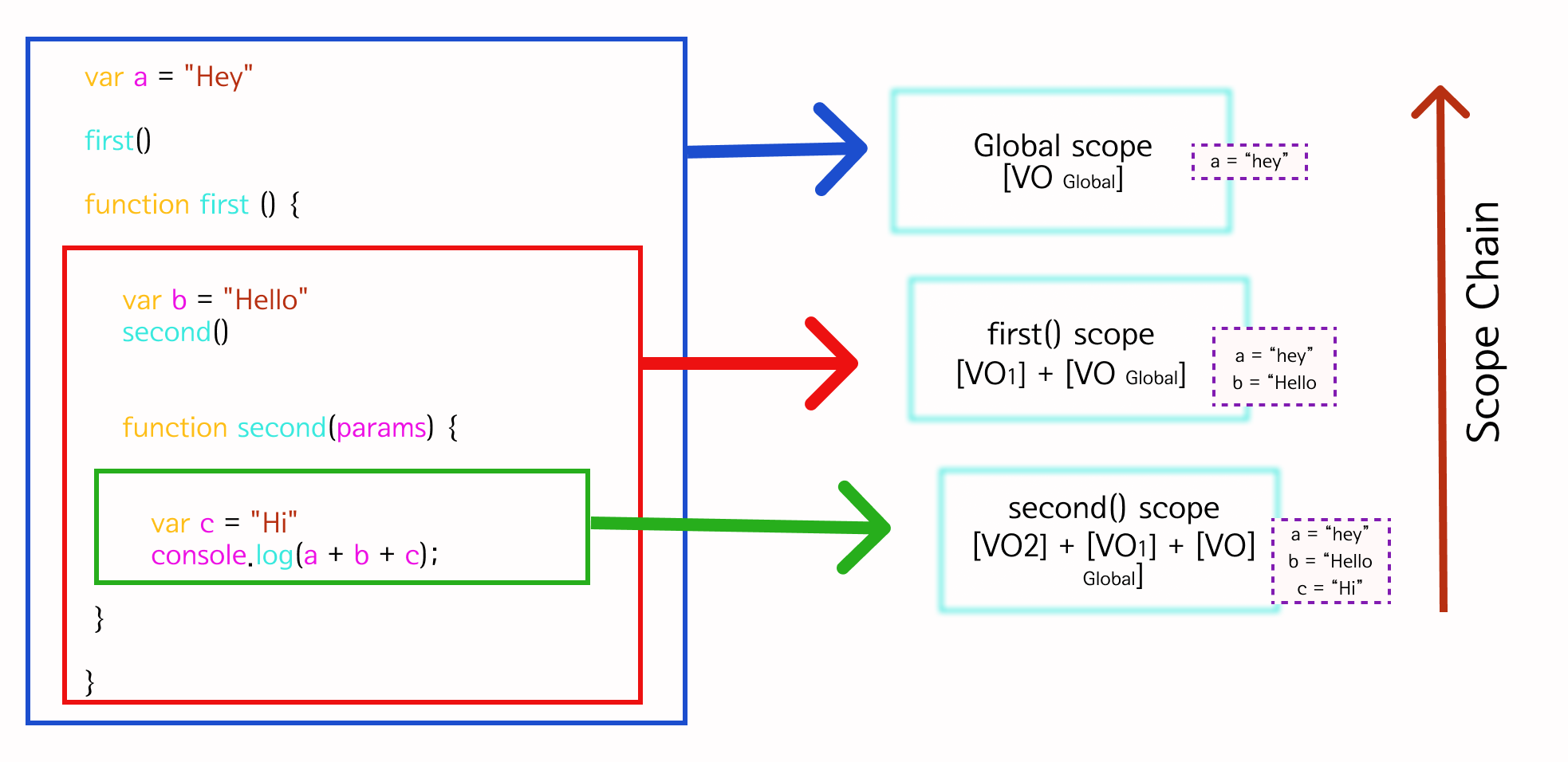

- On the right is the Global Scope. It is the default scope created when a

.jsscript is loaded and is accessible from all functions throughout the code. - The red box is the scope of the

firstfunction, which defines the variableb = 'Hello!'and thesecondfunction.

- In green is the scope of the

secondfunction. There is aconsole.logstatement which is to print the variablesa,bandc.

Now the variables a and b aren’t defined in the second function, only c. However, due to lexical scoping, it has access to the scope of the function it sits in and that of its parent.

In running the code, the JS engine will not find the variable b in the scope of the second function. So, it looks up into the scope of its parents, starting with the first function. There it finds the variable b = 'Hello'. It goes back to the second function and resolves the b variable there with it.

Same process for the a variable. The JS engine looks up through the scope of all its parents all the way to the scope of the GEC, resolving its value in the second function.

This idea of the JavaScript engine traversing up the scopes of the execution contexts that a function is defined in in order to resolve variables and functions invoked in them is called the scope chain.

Only when the JS engine can’t resolve a variable within the scope chain does it stop executing and throws an error.

However, this doesn’t work backward. That is, the global scope will never have access to the inner function’s variables unless they are returned from the function.

The scope chain works as a one-way glass. You can see the outside, but people from the outside cannot see you.

And that is why the red arrow in the image above is pointing upwards because that is the only direction the scope chains goes.

Creation Phase: Setting The Value of The “this” Keyword

The next and final stage after scoping in the creation phase of an Execution Context is setting the value of the this keyword.

The JavaScript this keyword refers to the scope where an Execution Context belongs.

Once the scope chain is created, the value of 'this' is initialized by the JS engine.

"this" in The Global Context

In the GEC (outside of any function and object), this refers to the global object — which is the window object.

Thus, function declarations and variables initialized with the var keyword get assigned as properties and methods to the global object – window object.

This means that declaring variables and functions outside of any function, like this:

var occupation = "Frontend Developer"; function addOne(x) {

console.log(x +1) }

Is exactly the same as:

window.occupation = "Frontend Developer";

window.addOne= (x) => {

console.log(x +1)};

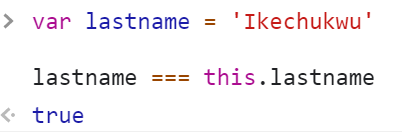

Functions and variables in the GEC get attached as methods and properties to the window object. That’s why the snippet below will return true.

"this" in Functions

In the case of the FEC, it doesn’t create the this object. Rather, it get’s access to that of the environment it is defined in.

Here that’ll be the window object, as the function is defined in the GEC:

var msg = "I will rule the world!"; function printMsg() {

console.log(this.msg);} printMsg(); // logs "I will rule the world!" to the console.

In objects, the this keyword doesn’t point to the GEC, but to the object itself. Referencing this within an object will be the same as:

theObject.thePropertyOrMethodDefinedInIt;

Consider the code example below:

var msg = "I will rule the world!"; const Victor = { msg: "Victor will rule the world!", printMsg() { console.log(this.msg) }, };

Victor.printMsg(); // logs "Victor will rule the world!" to the console.

The code logs "Victor will rule the world!" to the console, and not "I will rule the world!" because in this case, the value of the this keyword the function has access to is that of the object it is defined in, not the global object.

With the value of the this keyword set, all the properties of the Execution Context Object have been defined. Leading to the end of the creation phase, now the JS engine moves on to the execution phase.

The Execution Phase

Finally, right after the creation phase of an Execution Context comes the execution phase. This is the stage where the actual code execution begins.

Up until this point, the VO contained variables with the values of undefined. If the code is run at this point it is bound to return errors, as we can’t work with undefined values.

At this stage, the JavaScript engine reads the code in the current Execution Context once more, then updates the VO with the actual values of these variables. Then the code is parsed by a parser, gets transpired to executable byte code, and finally gets executed.

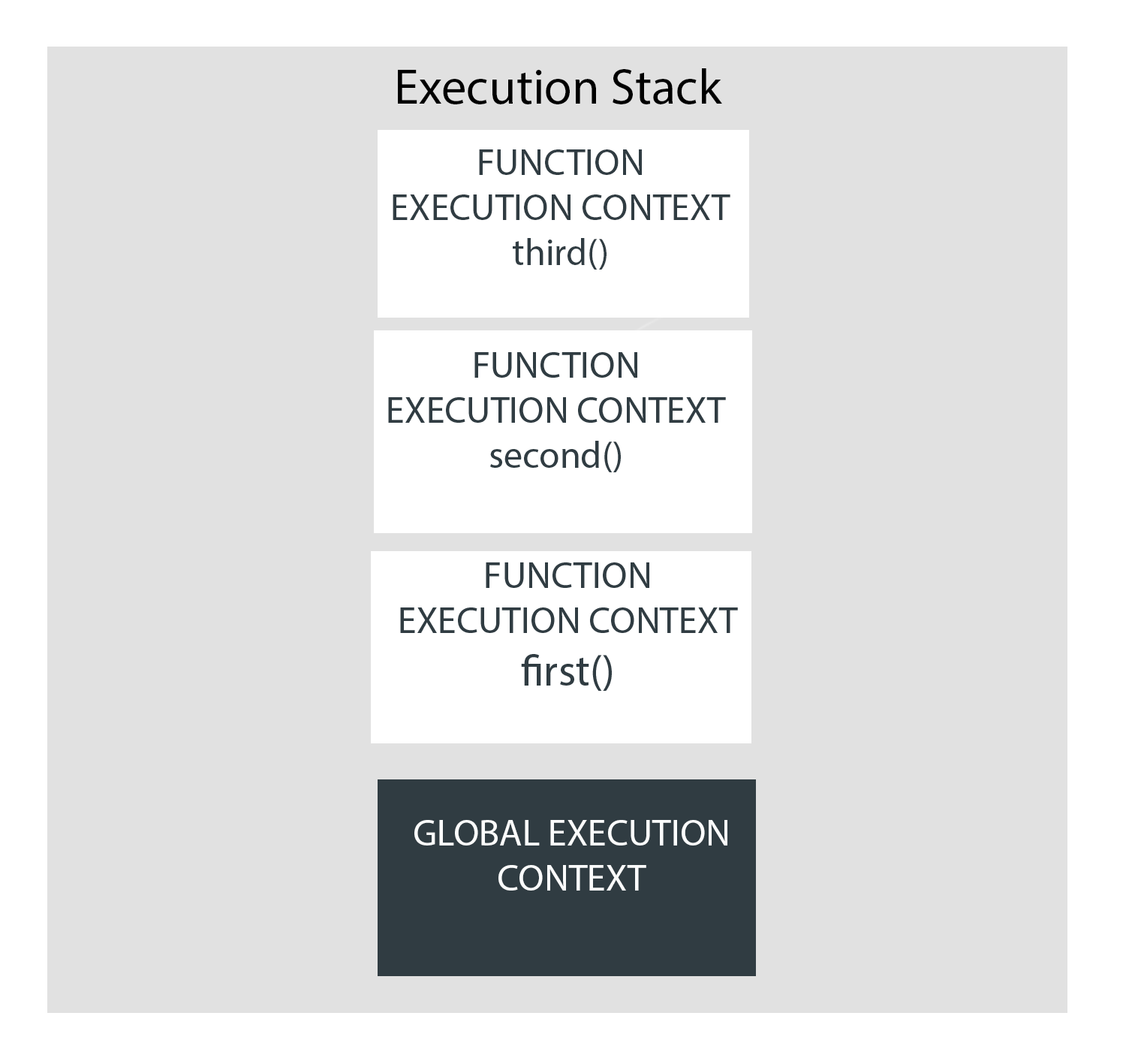

JavaScript Execution Stack

The Execution Stack, also known as the Call Stack, keeps track of all the Execution Contexts created during the life cycle of a script.

JavaScript is a single-threaded language, which means that it is capable of only executing a single task at a time. Thus, when other actions, functions, and events occur, an Execution Context is created for each of these events. Due to the single-threaded nature of JavaScript, a stack of piled-up execution contexts to be executed is created, known as the Execution Stack.

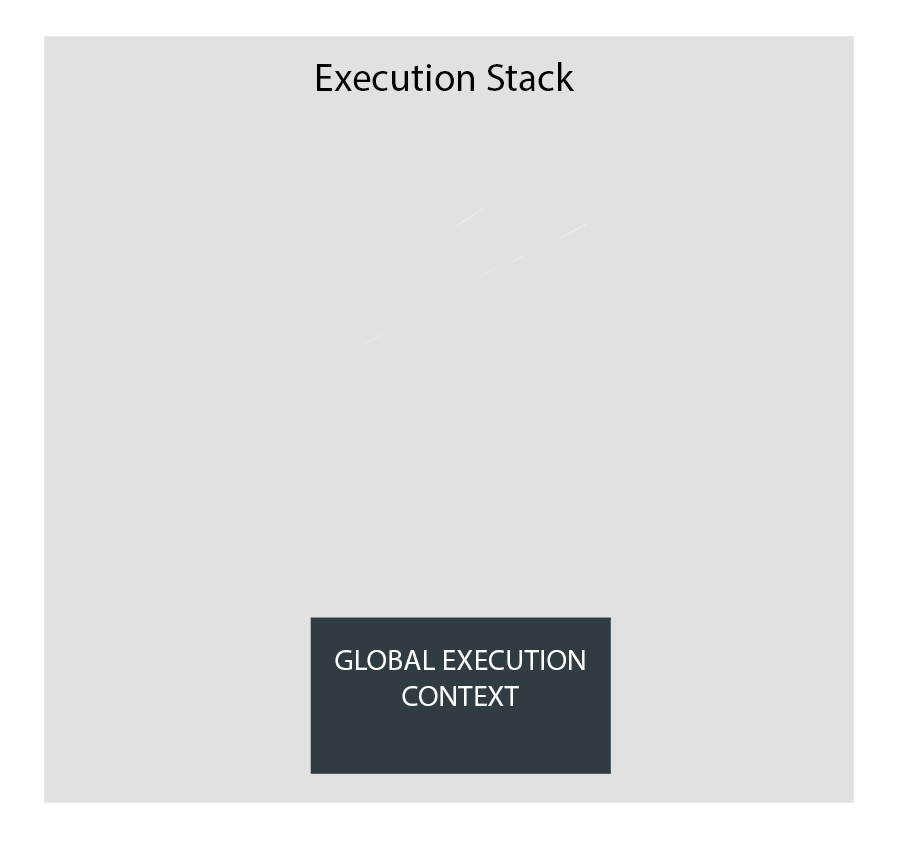

When scripts load in the browser, the Global context is created as the default context where the JS engine starts executing code and is placed at the bottom of the execution stack.

The JS engine then searches for function calls in the code. For each function call, a new FEC is created for that function and is placed on top of the currently executing Execution Context.

The Execution Context at the top of the Execution stack becomes the active Execution Context, and will always get executed first by the JS engine.

As soon as the execution of all the code within the active Execution Context is done, the JS engine pops out that particular function’s Execution Context of the execution stack, moves towards the next below it, and so on.

To understand the working process of the execution stack, consider the code example below:

var name = "Victor"; function first() { var a = "Hi!"; second();

console.log(`${a}${name}`);} function second() { var b = "Hey!"; third();

console.log(`${b}${name}`);} function third() { var c = "Hello!";

console.log(`${c}${name}`);} first();

First, the script is loaded into the JS engine.

After it, the JS engine creates the GEC and places it at the base of the execution stack.

The name variable is defined outside of any function, so it is in the GEC and stored in it’s VO.

The same process occurs for the first, second, and third functions.

Don’t get confused as to why they functions are still in the GEC. Remember, the GEC is only for JavaScript code (variables and functions) that are not inside of any function. Because they were not defined within any function, the function declarations are in the GEC. Make sense now 😃?

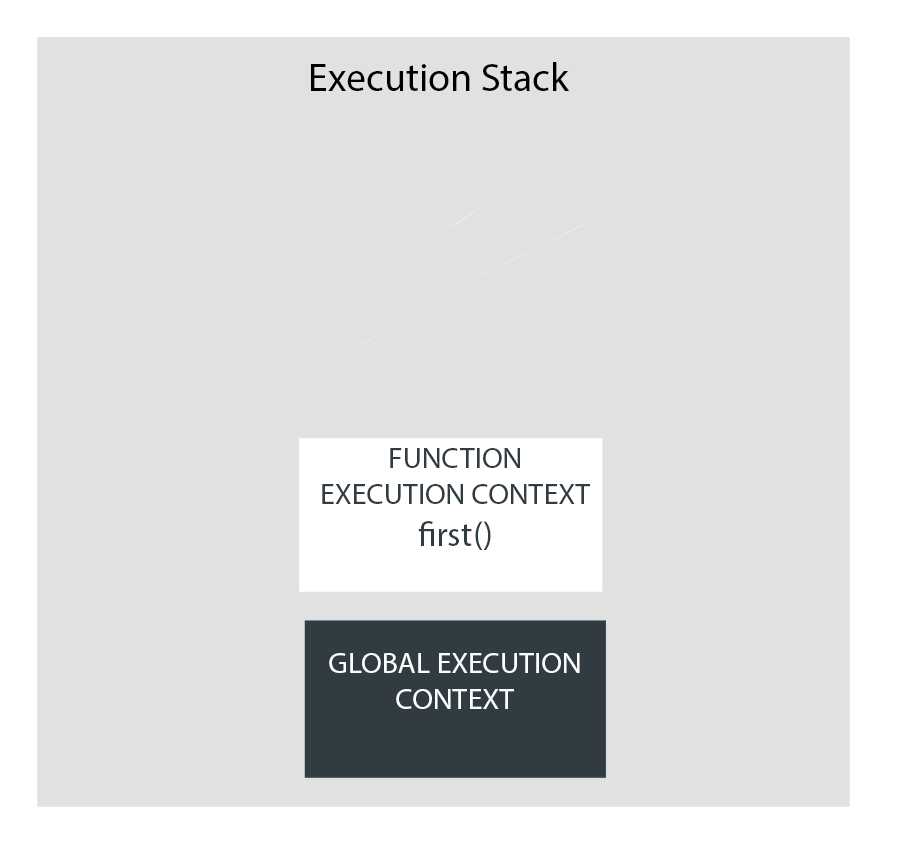

When the JS engine encounters the first function call, a new FEC is created for it. This new context is placed on top of the current context, forming the so-called Execution Stack.

For the duration of the first function call, its Execution Context becomes the active context where JavaScript code is first executed.

In the first function the variable a = 'Hi!' gets stored in its FEC, not in the GEC.

Next, the second function is called within the first function.

The execution of the first function will be paused due to the single-threaded nature of JavaScript. It has to wait until its execution, that is the second function, is complete.

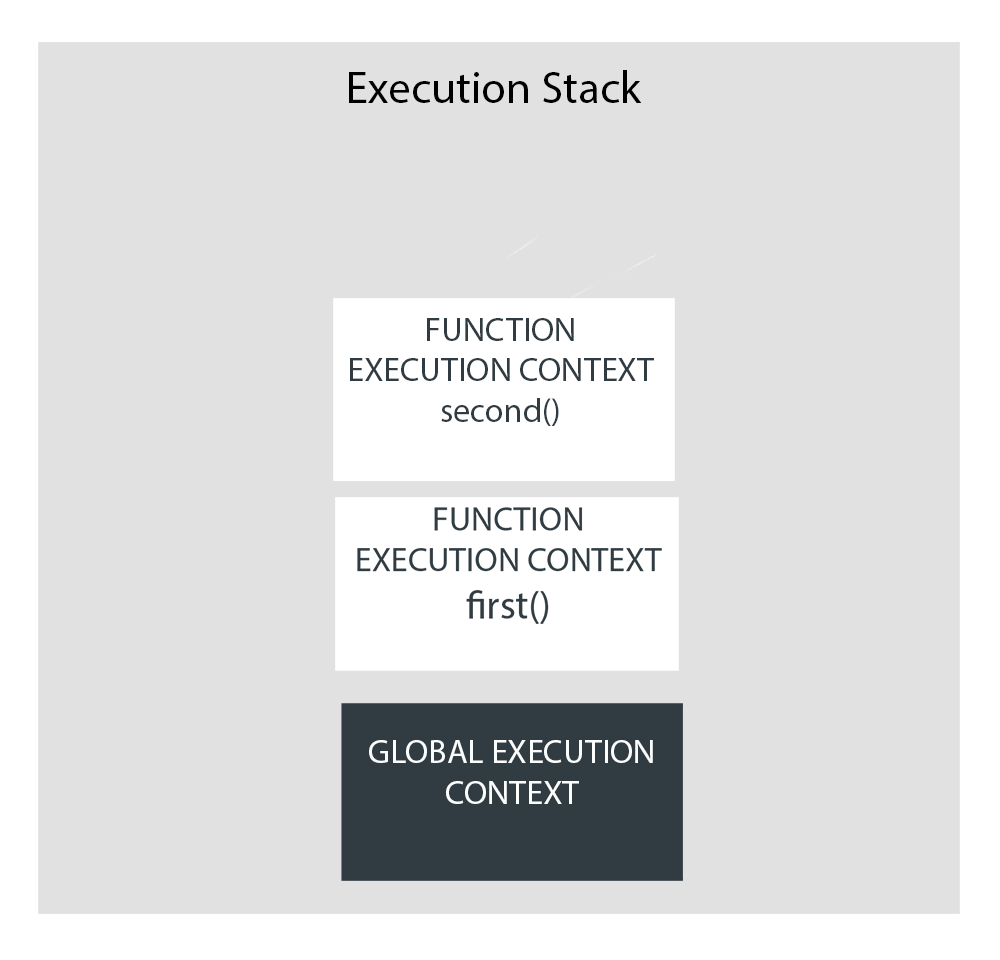

Again the JS engine sets up a new FEC for the second function and places it at the top of the stack, making it the active context.

The second function becomes the active context, the variable b = 'Hey!'; gets store in its FEC, and the third function is invoked within the second function. Its FEC is created and put on top of the execution stack.

Inside of the third function the variable c = 'Hello!' gets stored in its FEC and the message Hello! Victor gets logged to the console.

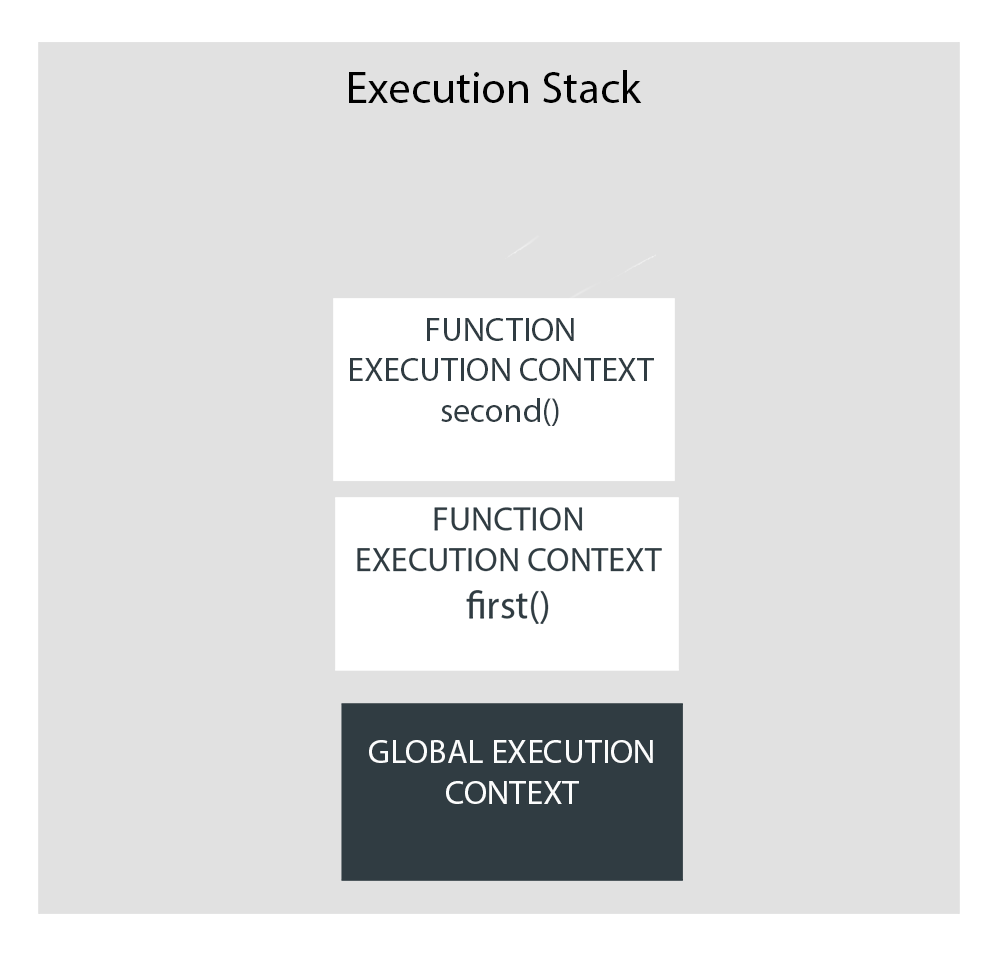

Hence the function has performed all its tasks and we say it returns. Its FEC gets removed from the top of the stack and the FEC of the second function which called the third function gets back to being the active context.

Back in the second function, the message Hey! Victor gets logged to the console. The function completes its task, returns, and its Execution Context gets popped off the call stack.

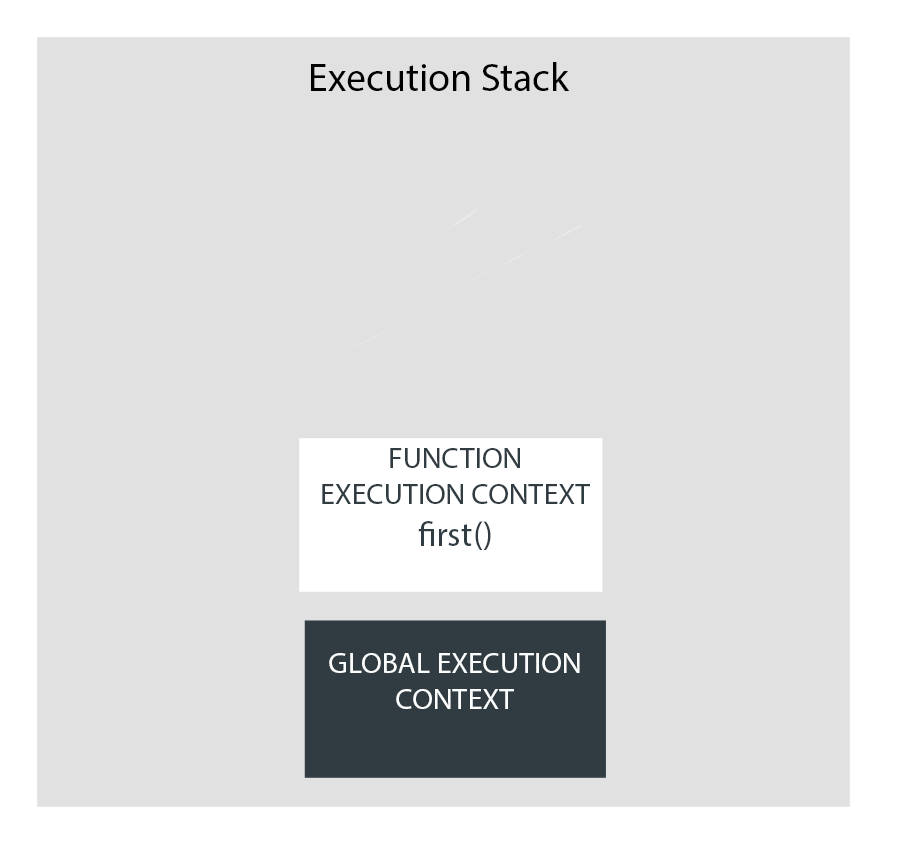

When the first function gets executed completely, the execution stack of the first function popped out from the stack. Hence, the control reaches back to the GEC of the code.

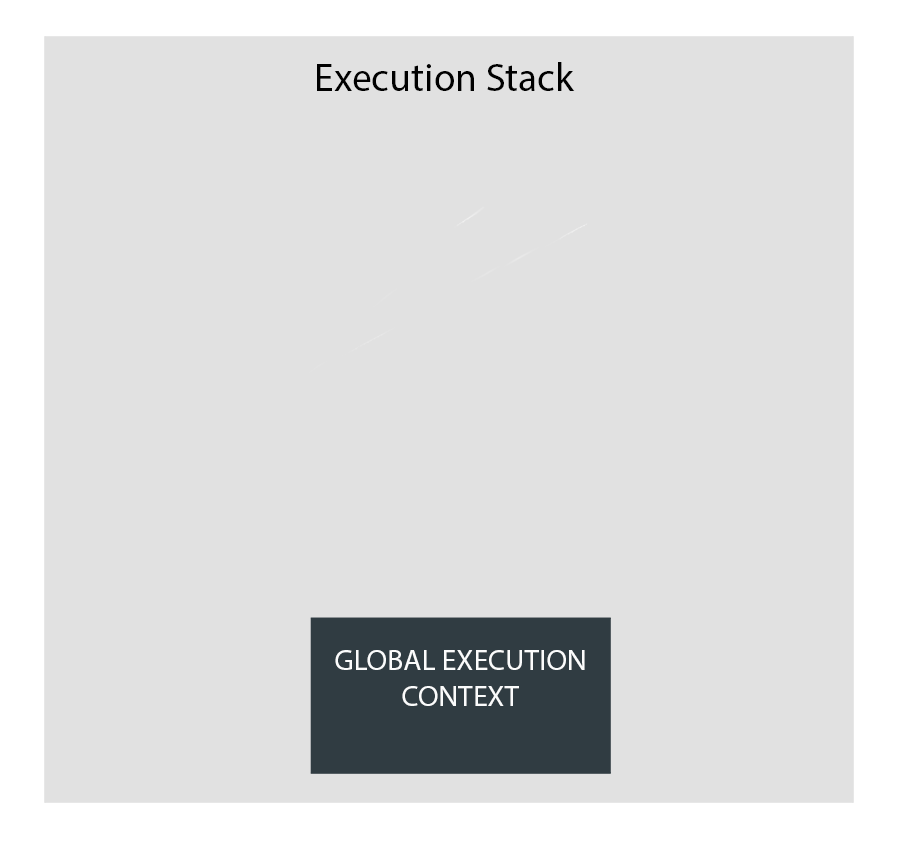

And lastly, when the execution of the entire code gets completed, the JS engine removes the GEC from the current stack.

Global Execution Context VS. Function Execution Context in JavaScript

Since you’ve read all the way until this section, let’s summarize the key points between the GEC and the FEC with the table below.GLOBAL EXECUTION CONTEXTFunction Execution ContextCreates a Global Variable object that stores function and variables declarations.Doesn’t create a Global Variable object. Rather, it creates an argument object that stores all the arguments passed to the function.Creates the this object that stores all the variables and functions in the Global scope as methods and properties.Doesn’t create the this object, but has access to that of the environment in which it is defined. Usually the window object.Can’t access the code of the Function contexts defined in itDue to scoping, has access to the code(variables and functions) in the context it is defined and that of its parentsSets up memory space for variables and functions defined globallySets up memory space only for variables and functions defined within the function.

Conclusion

JavaScript’s Execution Context is the basis for understanding many other fundamental concepts correctly.

The Execution Context (GEC and FEC), and the call stack are the processes carried out under the hood by the JS engine that let our code run.

Hope now you have a better understanding in which order your functions/code run and how JavaScript Engine treats them.

As a developer, having a good understanding of these concepts helps you:

- Get a decent understanding of the ins and outs of the language.

- Get a good grasp of a language’s underlying/core concepts.

- Write clean, maintainable, and well-structured code, introducing fewer bugs into production.

All this will make you a better developer overall.

Hope you found this article helpful. Do share it with your friends and network, and feel free to connect with me on Twitter and my blog where I share a wide range of free educational articles and resources. This really motivates me to publish more.

Thanks for reading, and happy coding!

freeCodeCamp is a donor-supported tax-exempt 501(c)(3) charity organization (United States Federal Tax Identification Number: 82-0779546)

Our mission: to help people learn to code for free. We accomplish this by creating thousands of videos, articles, and interactive coding lessons – all freely available to the public.

Donations to freeCodeCamp go toward our education initiatives, and help pay for servers, services, and staff.

You can make a tax-deductible donation here.

RELATED POSTS

View all